Spoiler alert: There was a happy ending. But Augury’s search for Product-Market Fit was preceded by a bumpy ride complete with a surprising pivot. Product Manager at the time, Noam Green, looks back to share the learnings – and the stories behind the winding road towards innovation.

As Augury develops new products and services that seek to unlock full Production Health, it’s an appropriate time to look back at where it all started: Machine Health. The story is not only a shiny case study in successfully finding Product-Market Fit (and later, Crossing the Chasm – which will be covered in a future post). It also shows the foundational work on which a promising startup could later transform into a full-blown scale-up – and one of Industrial AI’s first unicorns.

“I think our journey really has distinct characteristics that might be relevant for many others working as product managers,” says Noam Green, currently VP of Product for Machine Health at Augury. He is the perfect person to tell the tale since he led the discovery work and helped develop Augury’s initial product for the industrial space. He also happens to be a hilarious storyteller. Below he shares some key moments and insights.

Get your definitions right (and find a real and painful problem)

“My job is about making sure we’re tackling the right problems and opportunities in order to design something that creates value for customers and on which you can build a successful business. And ‘Product-Market Fit’ is one of those terms that nearly everyone with my job uses. And it can sometimes mean something slightly different for different people – and it’s usually more centered around the consumer space than B2B.”

“And that’s what you need to find: a problem so painful that people are willing to invest in solving it with time and money.”

“Smarter people like Marty Kagan and Paul Graham can probably define it better. But essentially – and forgive me for stating the obvious – it’s a combination: bringing together ‘product’ and ‘market’ and making sure they ‘fit’. You have to find a real, valuable problem to solve in the market. And the solution must be effective, repeatable, scalable, viable and doesn’t cost heaps of money. One example I use is bilingual keyboards. My personal life is in Hebrew and my professional life is in English. Each time I have to switch keyboards. It’s horrific! It’s a pain! But I’m used to it and not sure if I would pay for a solution. And that’s what you need to find: a problem so painful that people are willing to invest in solving it with time and money.”

Definitions may differ between personas

“Getting people to pay is especially hard in B2B, because you usually have to deal with two personas that are equally important. The one signing the check will define a problem and see the solution in a certain way. And their currency is budgets. Then, there’s the person actually using the tool. Their currency is not money but time. So, you have to strike Product-Market Fit with both. Both the product and the experience need to make sense – while also making business sense.”

You don’t have to be a tech nerd to develop a tech product

“I am not the classic product manager. I’m actually completely the opposite of a technology geek. I believe the relationship between humans and technology is currently unbalanced – and not in the favor of humans. While technology could be the most efficient servant humans have ever dreamed of, it’s now more of a horrible dictator of time. It’s controlling our lives more than helping our lives. So, even my father is more of an early adopter than me [laughter]. You won’t see me rent a scooter with my phone.”

“But this attitude is actually one of the biggest advantages I have when working on new products – especially in environments like the industrial space. The eventual users are also generally not classic early adapters. They just want to stop firefighting and get home to their families on time. Who cares about a flashy new dashboard?”

“While technology could be the most efficient servant humans have ever dreamed of, it’s now more of a horrible dictator of time.”

Be willing to switch markets

“We only started to really engage users in the fourth quarter of 2018. We had already introduced our Auguscope and Halo in mid 2017, but our engagement levels were literally at zero.

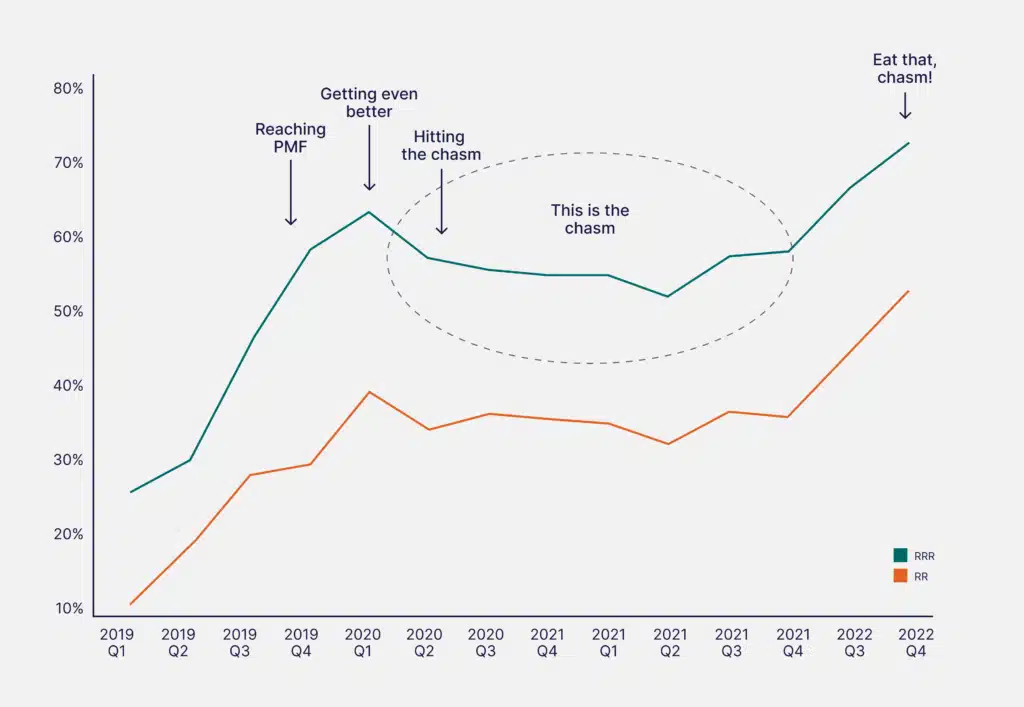

Then in mid 2018, we pivoted: away from commercial facilities to manufacturing and industrial production equipment. And boom, things started going ridiculously well. Look at the graph, it tells a story: a story with a huge hockey stick. Flat, flat, flat, flat, skyrocketing – that’s Product-Market Fit. That’s when we celebrated. But we still had a lot of work to do.”

When pivoting, pivot with gusto

“I spent like five years before joining Augury at five different early-stage startups – one was even mine. Basically, each one would die a year in, and I’d get fired – or fire myself. That’s the reality of startups. I would just find another. So, I had a lot of experience working on products before Product-Market Fit – and most failed miserably. And whenever a startup was running out of money, they would pivot to something new: to find a new nail to hit with their hammer before they had to turn out the lights. And actually, life is much tougher post-pivot than it is when you are starting from scratch.”

“It’s more of a weird dance of holding a hammer while looking for nails – thinking that maybe you can just switch the handle or just get rid of the head.”

“When Augury pivoted to the industrial space, we had zero revenue coming from that space. We also did not have the resources to maintain our old customers while building something totally new. So that’s one challenge: not getting pulled into things that are urgent but not important.”

“At the same time, you have the technical challenge: looking to somehow leverage the IP you already have for your new direction. It’s less about looking for a problem to solve – which all the books tell startups to do. But this is not realistic. There are investors, IP, customers… It’s more of a weird dance of holding a hammer while looking for nails – thinking that maybe you can just switch the handle or just get rid of the head.”

“And Augury was very brave. We retained our fundamental IP and idea around listening to machines. But then we developed the new product in silo and really rethought everything from the ground up without worrying about what current customers would say. It’s not easy: we had 40 or 50 people in the company who were all emotionally invested in the solution and our customers. But I think that’s where other startups often fail: not daring to fully embrace a new strategy when they pivot.”

Rethink your product from ground up, do the homework, and ask the right questions (AKA: It’s okay to be rude)

“When you are in pre Product-Market Fit, you don’t optimize for revenue but for validated learning. And that’s easier said than done. Especially in post-pivot. In our case, we had started selling early and our product was lagging. And our initial manufacturing customers already had ideas on how things could be done better. But you have to be stubborn to not follow their requests before really taking the time to deeply understand their needs.”

“I literally ask them why they wanted to go further with a certain approach. What value are you seeing from this thing we just shipped? How did it change the way you work? How are you going to measure success? And how are you going to measure the ROI? Don’t worry about hurting anyone’s feelings or ignoring their requests – because you might lose this one customer, but you will win the 500 that follow because you truly understand their needs.”

Map it out

“So, we started doing exploration discovery and talking to many, many people from the industrial space at different levels – VPs, VPs of operations, maintenance managers, operators, process engineers – to sniff around for potential value drivers that fit with the IP we had.

“From this presentation from November 2018 – just around the time we found Product-Market Fit – it shows the seven key selling points, or value drivers, brought up during the discovery process. These included the still very familiar ‘avoiding unplanned downtime’, as well as enabling quality maintenance, near real-time root cause analysis, etcetera…”

“So now the question became: Which one of these selling points are close to our core competency, and have significant financial potential? From there we had to look at who is the person we’re solving a problem for? The maintenance operations, process engineering, plant manager, the corporate level, etc… And then we decided this is the person we want to focus on…” “And I can tell you, four years later, that with more than 100 manufacturing customers and working in more than 30 countries globally, we chose well.”

Try to help someone with a painful problem

“Once you have your value drivers mapped out onto a particular vertical that makes sense, you need to find someone who has very distinct characteristics. For us it became obvious that it should be about continuous manufacturing not batch manufacturing. It had to be high-demand environments that worked 24/7 – where it’s not possible to compensate for lost productivity or unplanned downtime on the weekends. And we started to think more about specific verticals and how we are going to solve it for this specific person?”

Solution guidelines: back to learning

“Once you have the persona you want to focus on, you want to get a deep understanding of them. You don’t want to talk about a hypothetical future; you want to talk about the present in the past. You don’t want to ask what their perfect hybrid Hebrew-English keyboard would look like. But you would ask: When was the last time that you typed a message in Hebrew? Was it annoying? Yes? Why? You want concrete examples and whether they did anything practical in order to solve that problem. You want to find out if they are already doing something proactively to solve the problem.”

Look for the emotional aspect

“Part of the solution guidelines is the emotional aspect: What is their ‘emotional job-to-be done’? With maintenance managers, we discovered that their emotional motivation sounds something along the lines of: ‘There’s nothing that I hate more about my job than sitting with my family on a Saturday night, and getting a phone call from the site telling me that a machine crashed.’ This is a very emotional statement. So, we can use it to potentially create a very strong emotional attachment. And actually, we built the entire interface with this in mind: around the notion of ‘Machines to notice’ – because if you don’t pay attention right now, you might get a call while you’re sitting down with your family for dinner.”

“Have you ever tried replacing a bearing under a gazillion-degree fire? With hot oil dripping on your forehead?”

“Now years later, it still resonates. I was visiting a site the other day and as usual I am fishing to find problems to solve: ‘What sucks?’ And a couple of guys on the maintenance team came in and said, ‘Nothing! It’s amazing. We love it.’ And of course, I don’t buy this and keep pushing. And one said, ‘Have you ever tried replacing a bearing under a gazillion-degree fire? With hot oil dripping on your forehead?’ I hadn’t and frankly don’t want to. ‘Well, now I get to do it when the plant has planned downtime and the temperature is normal.’ The guy was really happy.

“Finding Product-Market Fit was amazing. But in reality, it was just the beginning of the work to do. Augury’s aspiration wasn’t to be a solution that made a few people happy, we wanted to transform the industry. To do that, we had to figure out the next big challenge: scale…” Tune in next time for: Crossing The Chasm… Meanwhile, read: ‘10 Reasons Why Augury’s AI Is Exciting More People Than Just Manufacturers‘.